Mo Baala : A Conversation

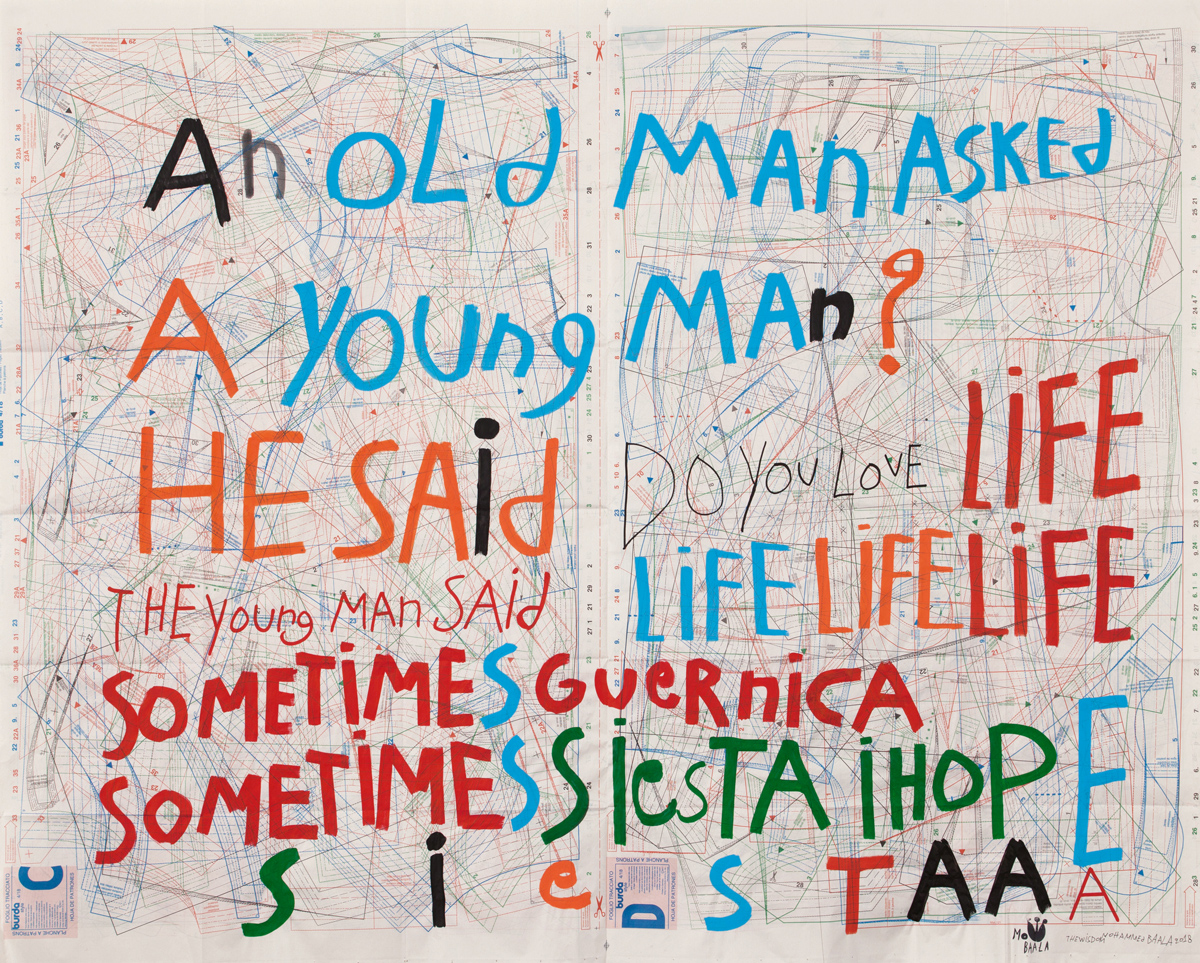

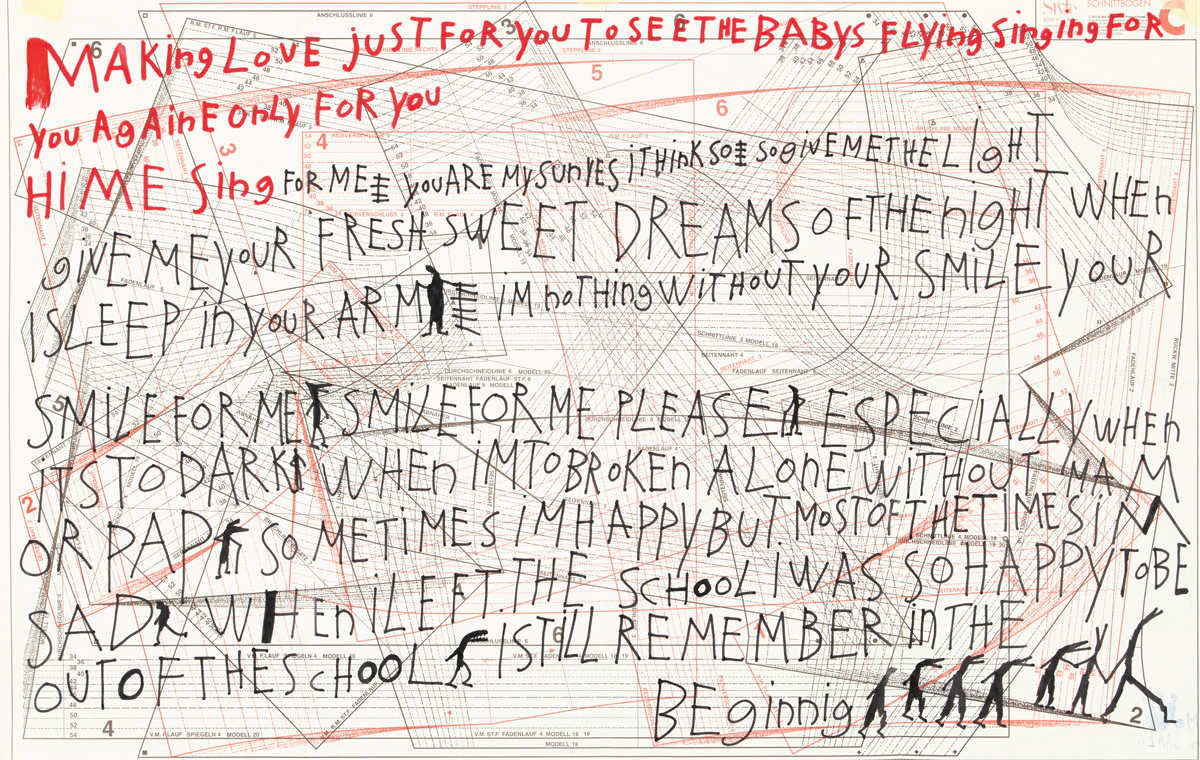

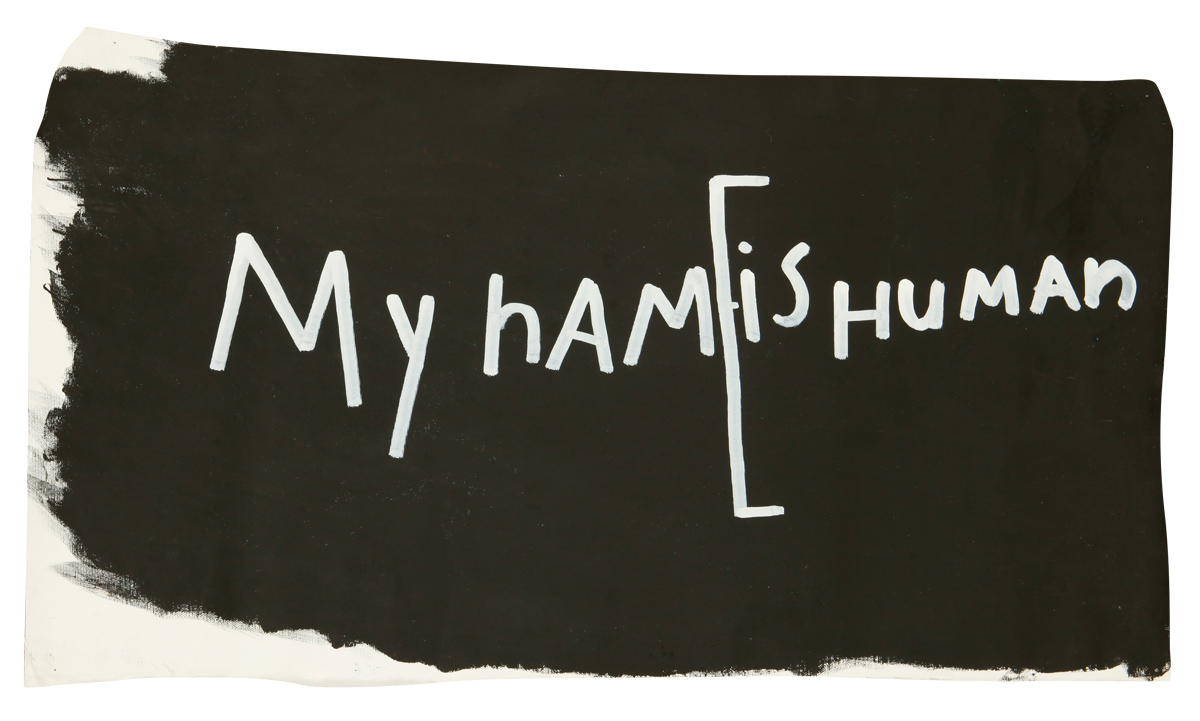

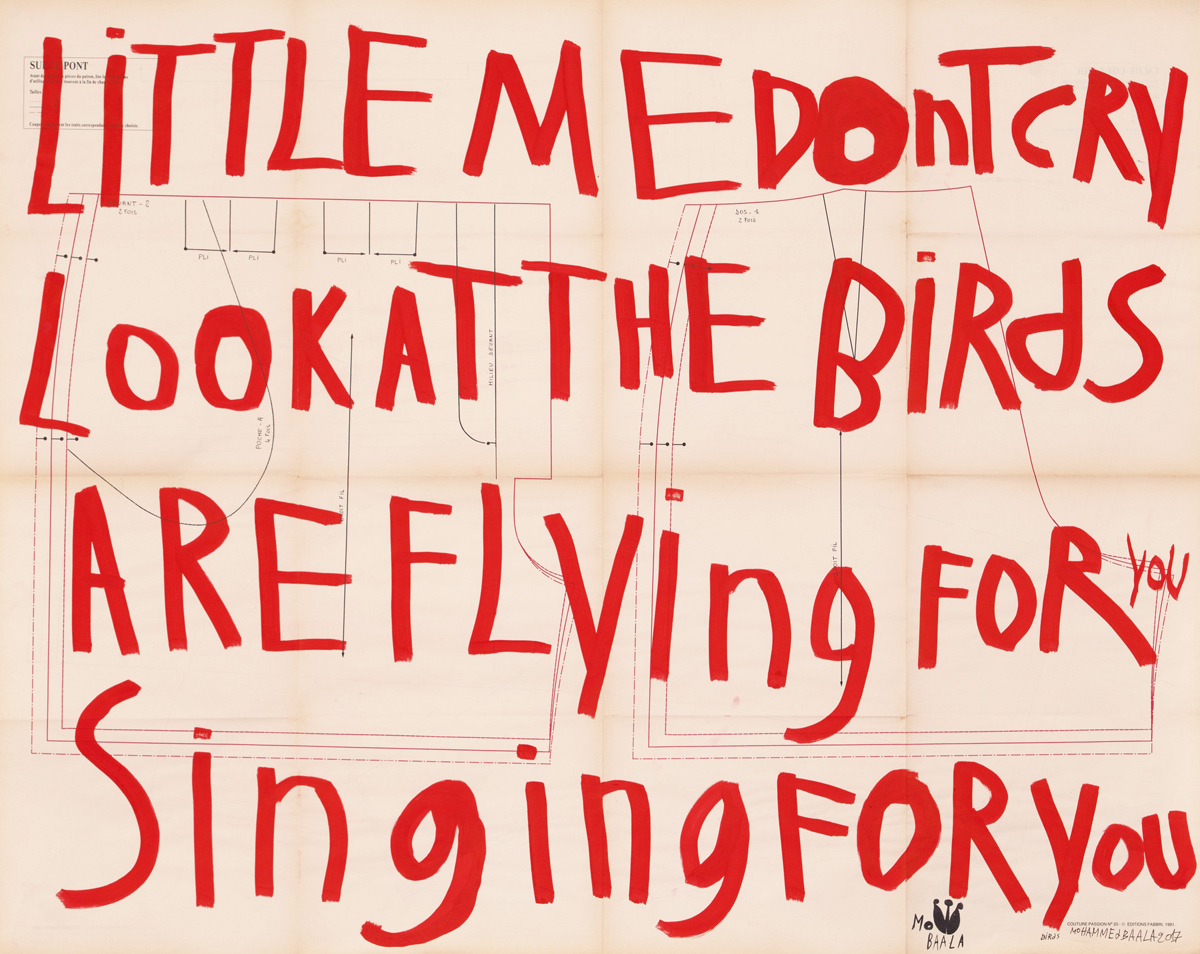

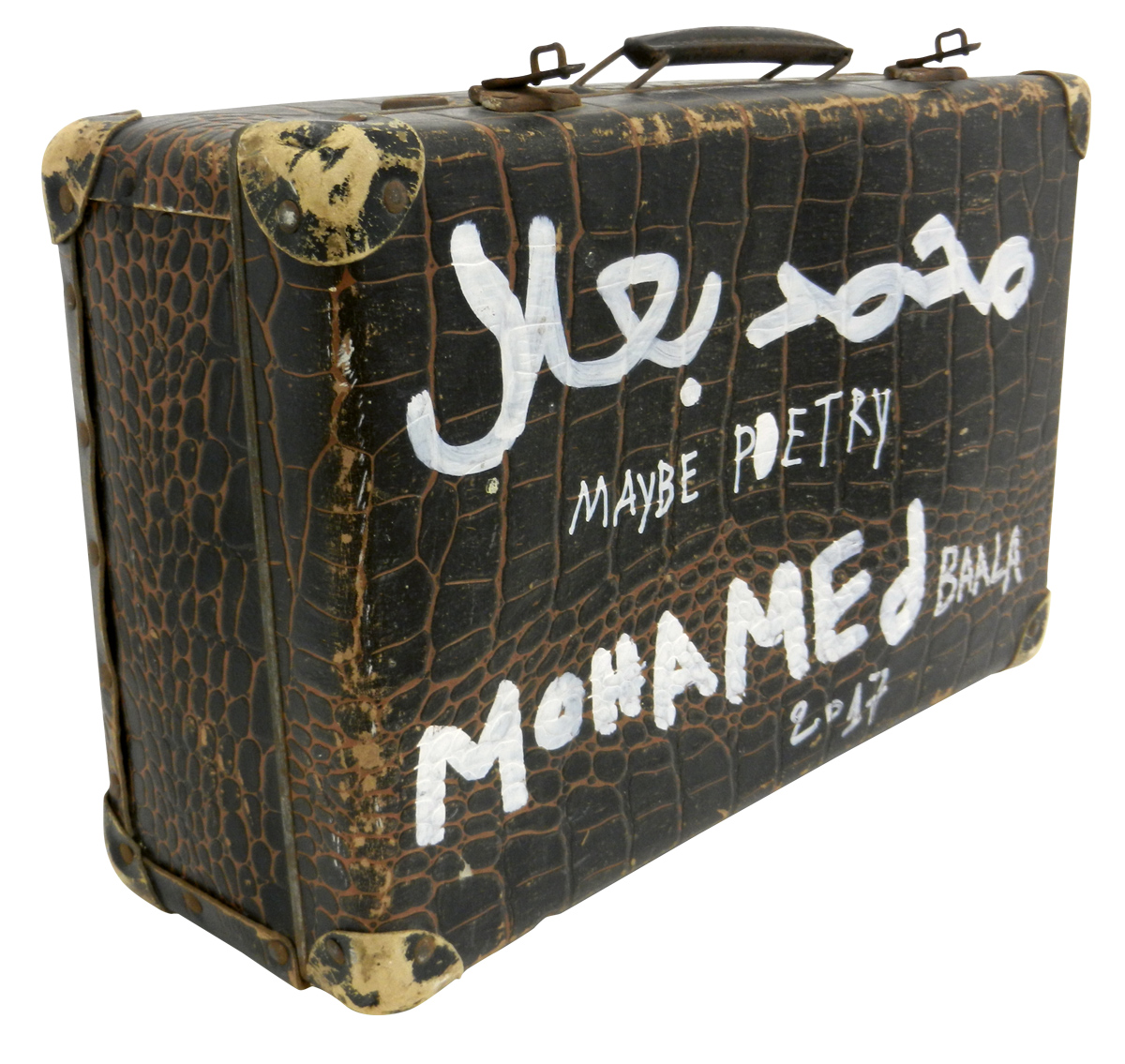

Often the details provided at an exhibition inhibit a viewer’s ability to decide for themselves what a work is about or feel content with their perception of a piece. Constant streams of information have implied that there is a right and wrong. For some artists this is the case, but for Mo Baala, it is not. He welcomes alternative understandings and equally ensures that there is no ‘correct’ conclusion. This thought- piece is based on an interview I had with Mo Baala in March 2018, in which he said, “My purpose as an artist is to propose possibilities…I don’t like when the subject colonises you.” As such, this article only covers some themes represented in the work broadly and focuses more on Mo Baala’s creative process.

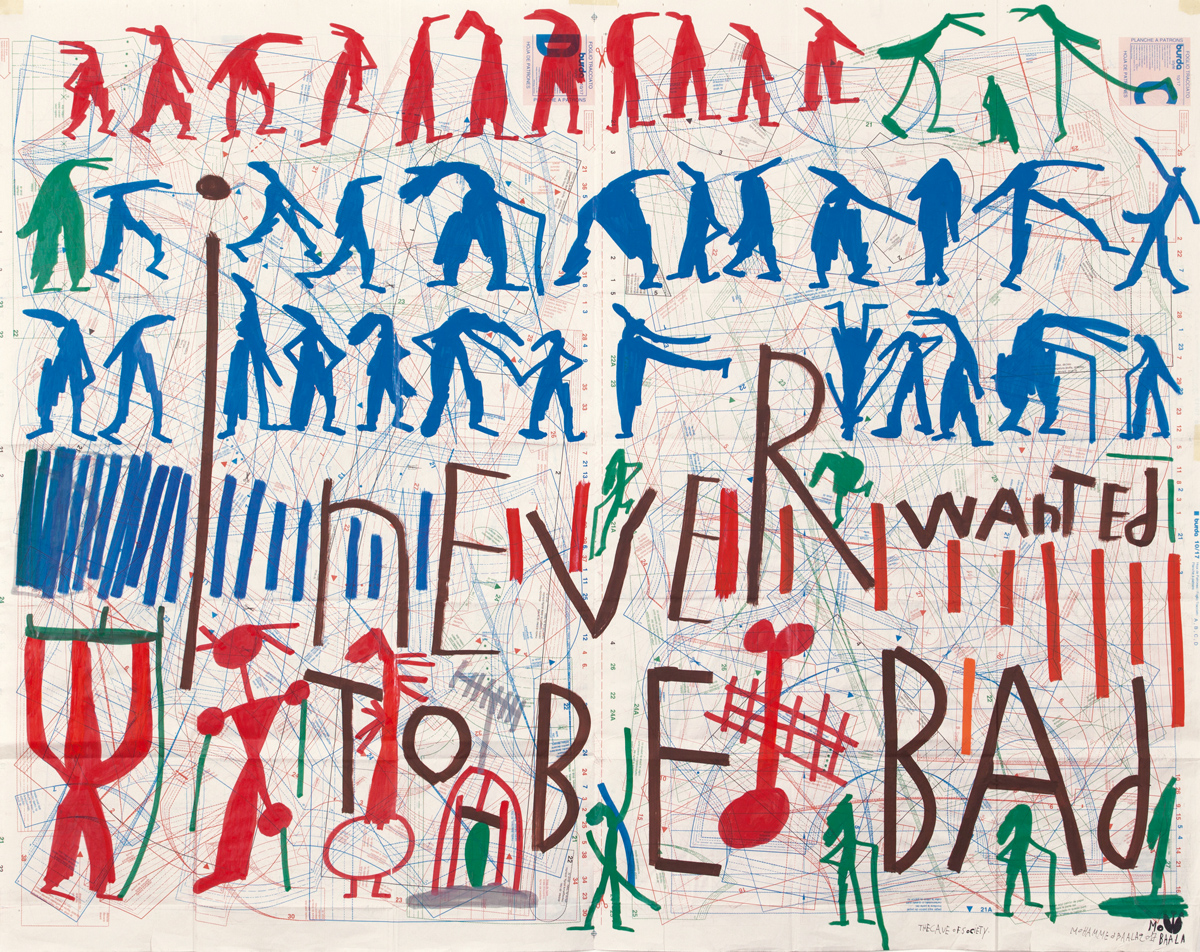

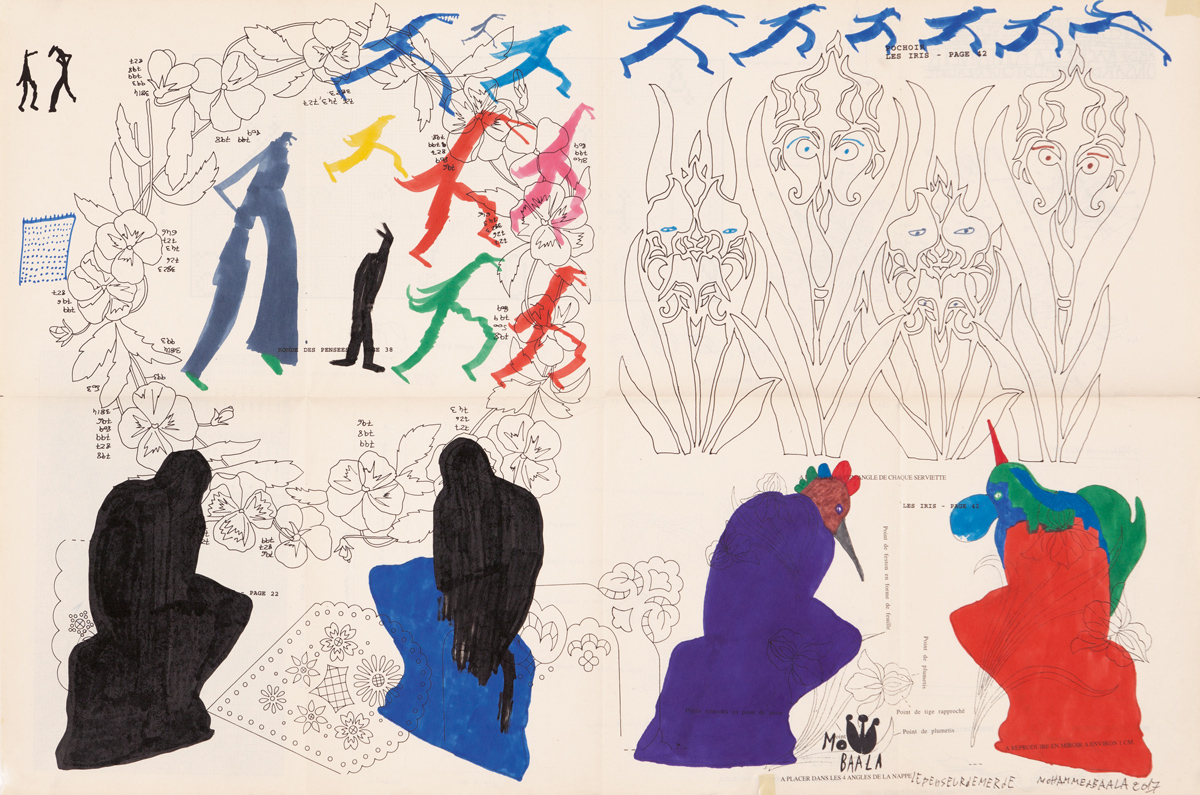

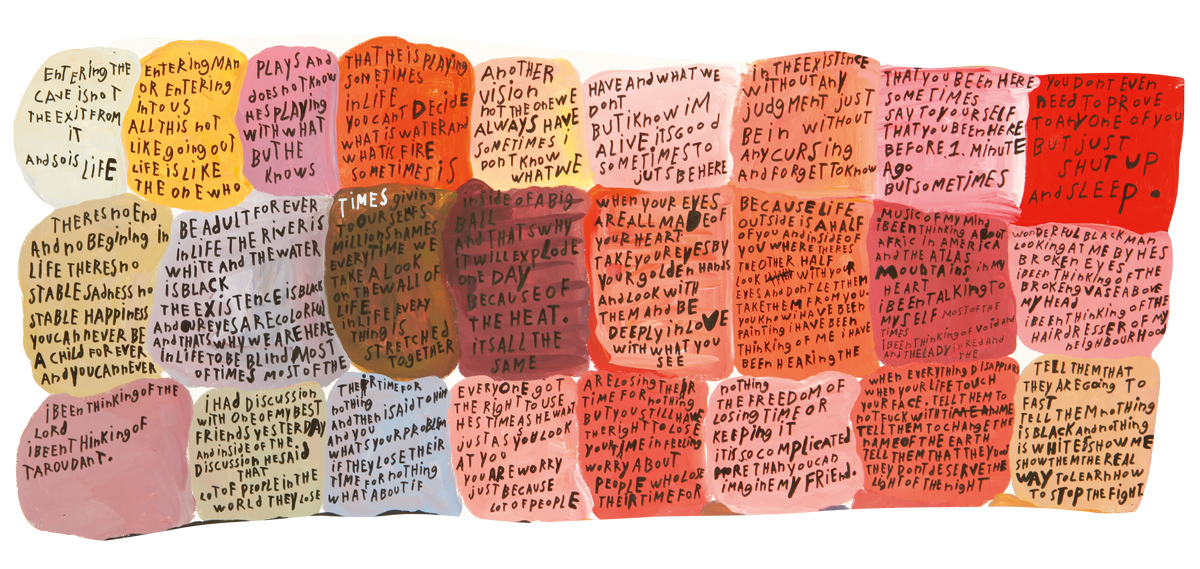

Balance: a word that has continually come to mind when I have thought about Mo Baala’s life and work following our conversation. He strives for balance, or “half- half” as he says. While creating, he plans, but also welcomes disorder. Likewise, he solves problems, while also creating new ones. For Mo Baala the creative process is a “sensitive situation” between opposites.

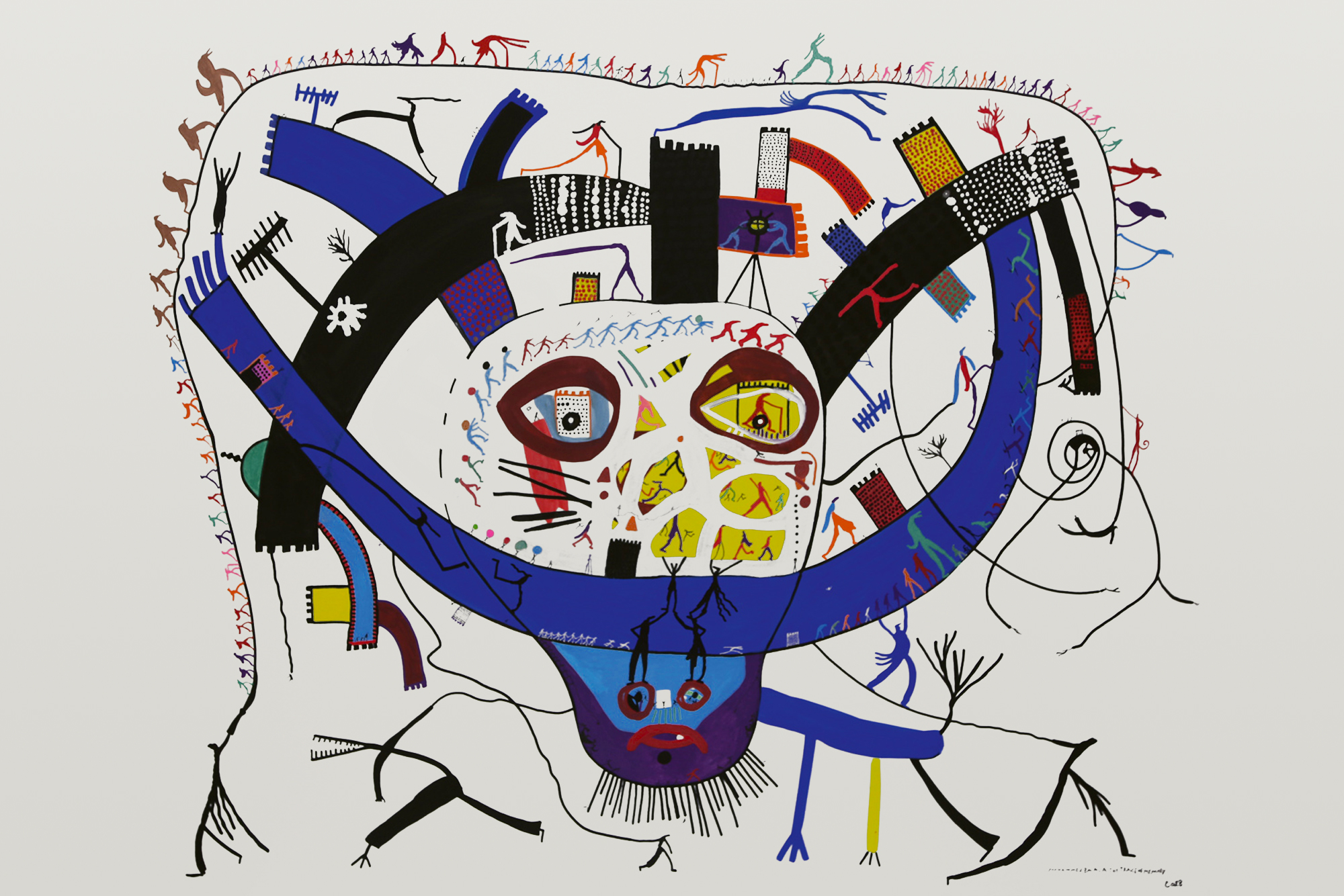

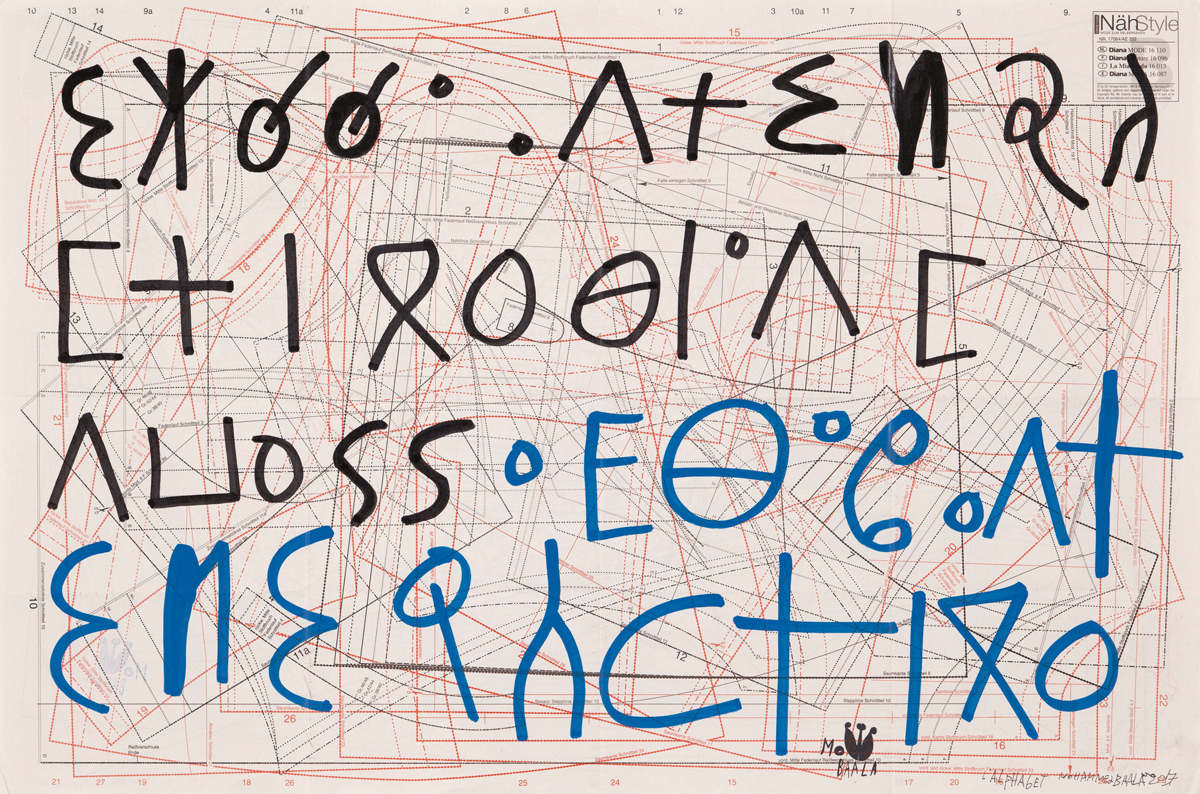

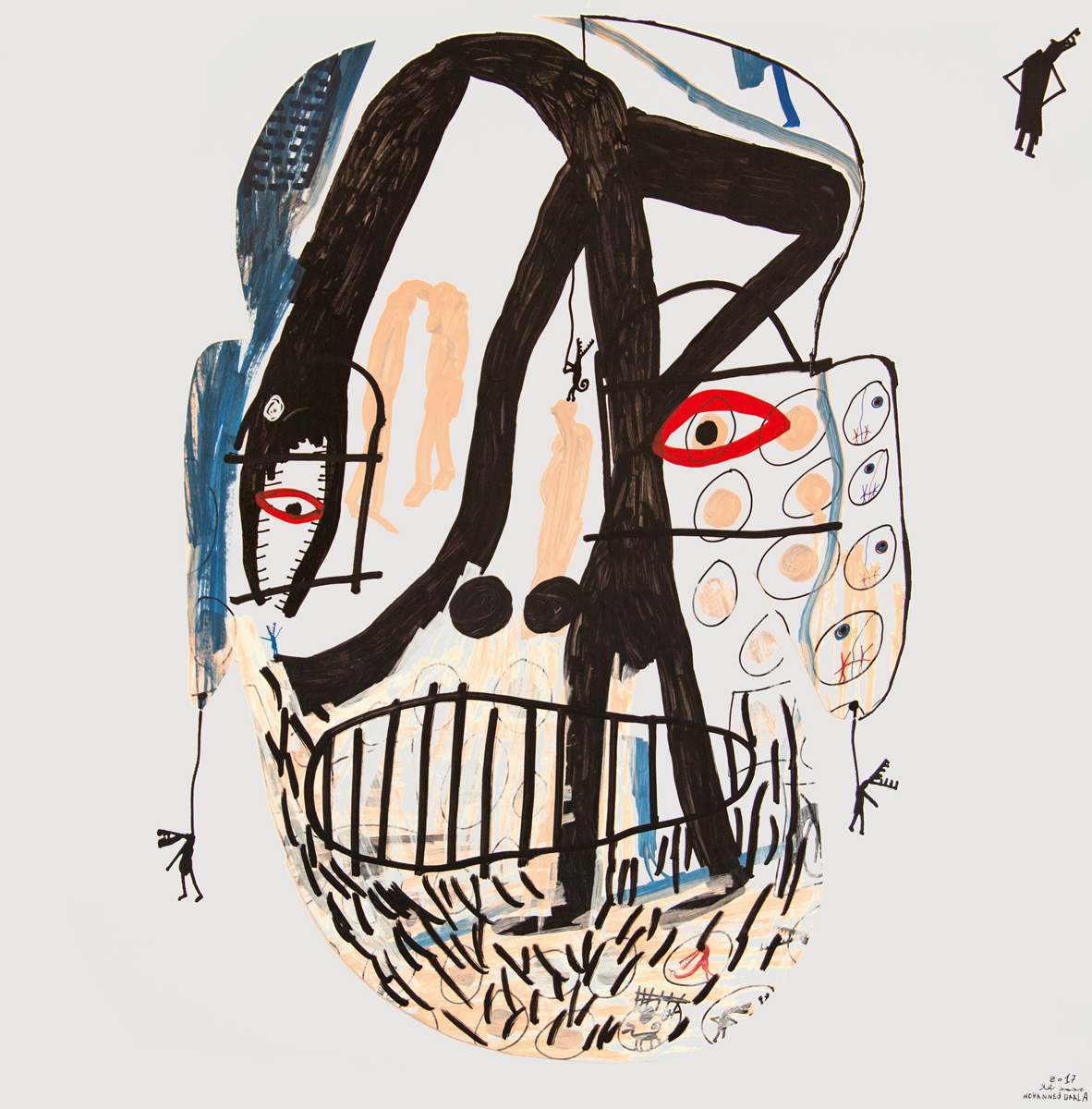

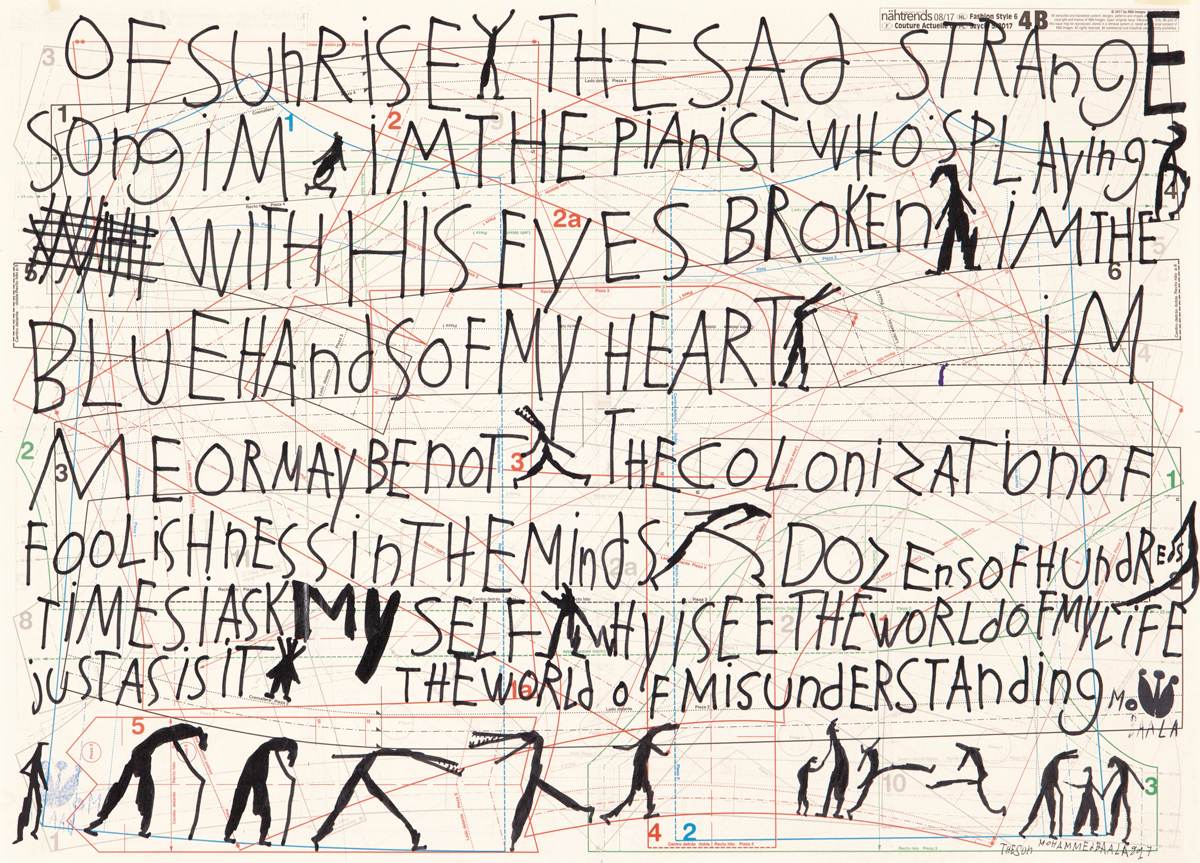

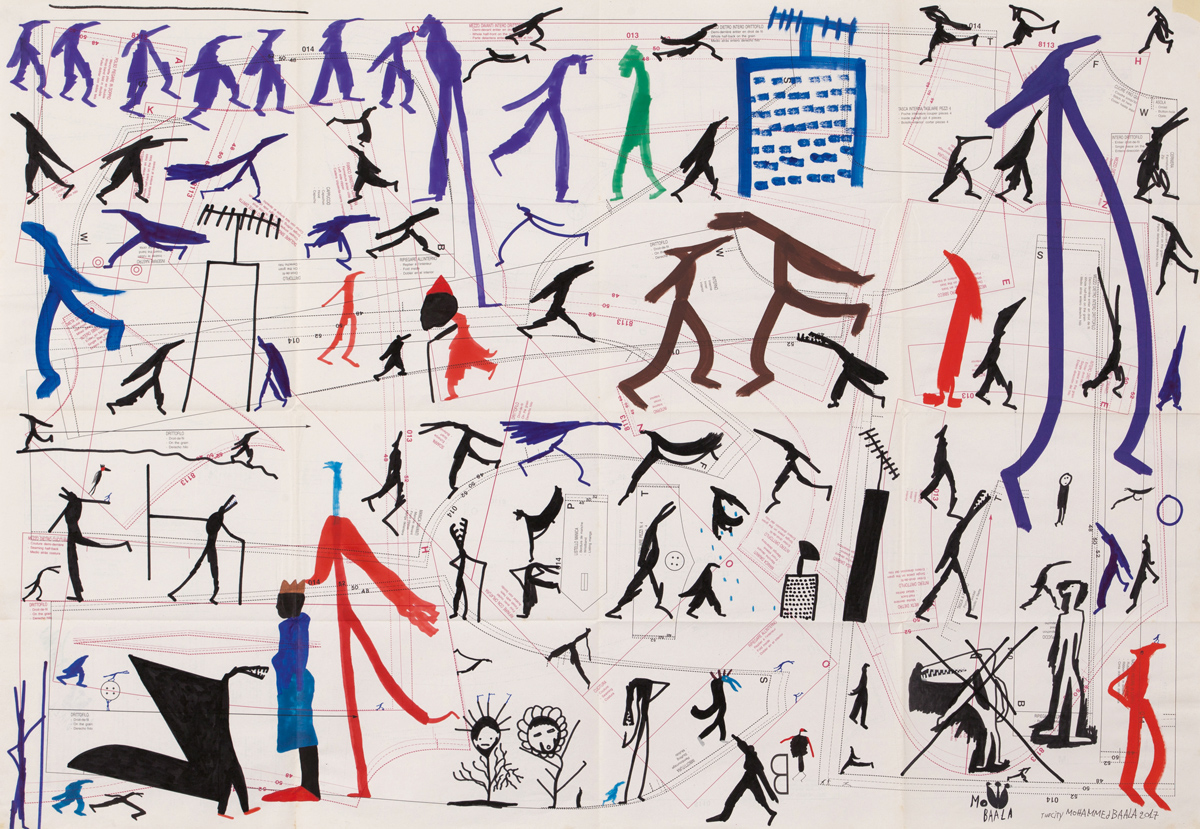

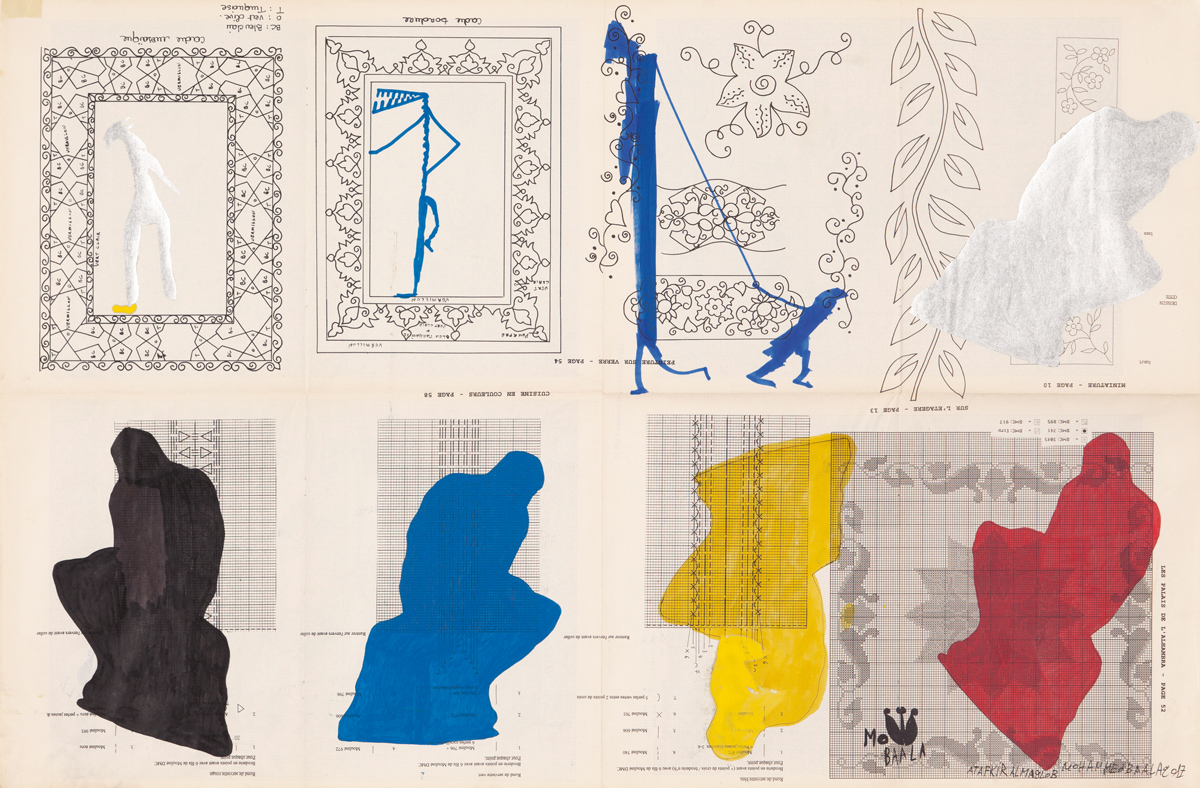

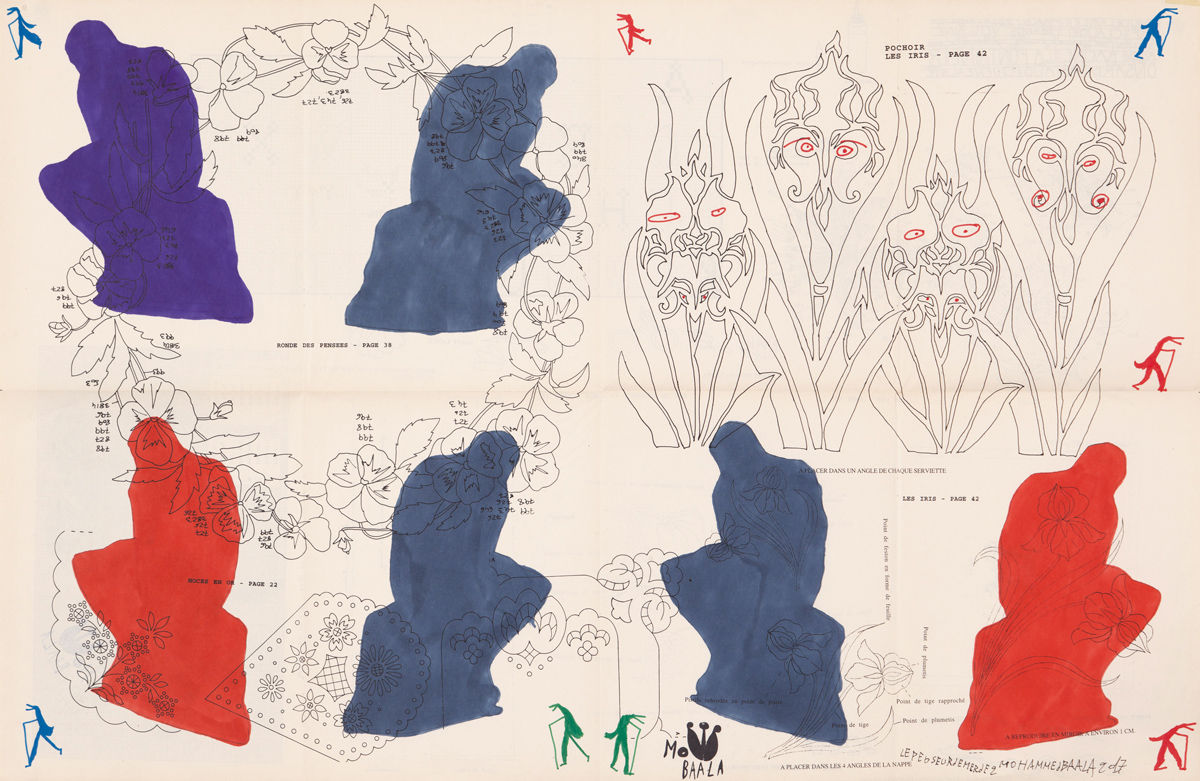

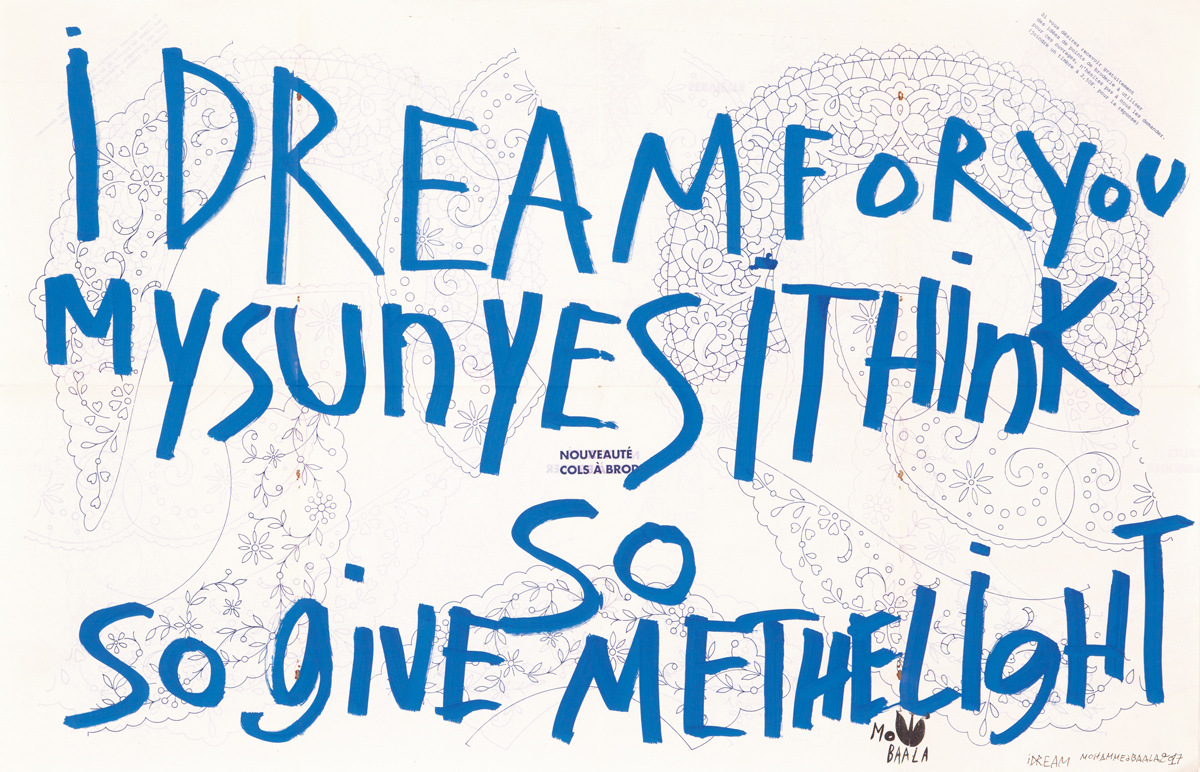

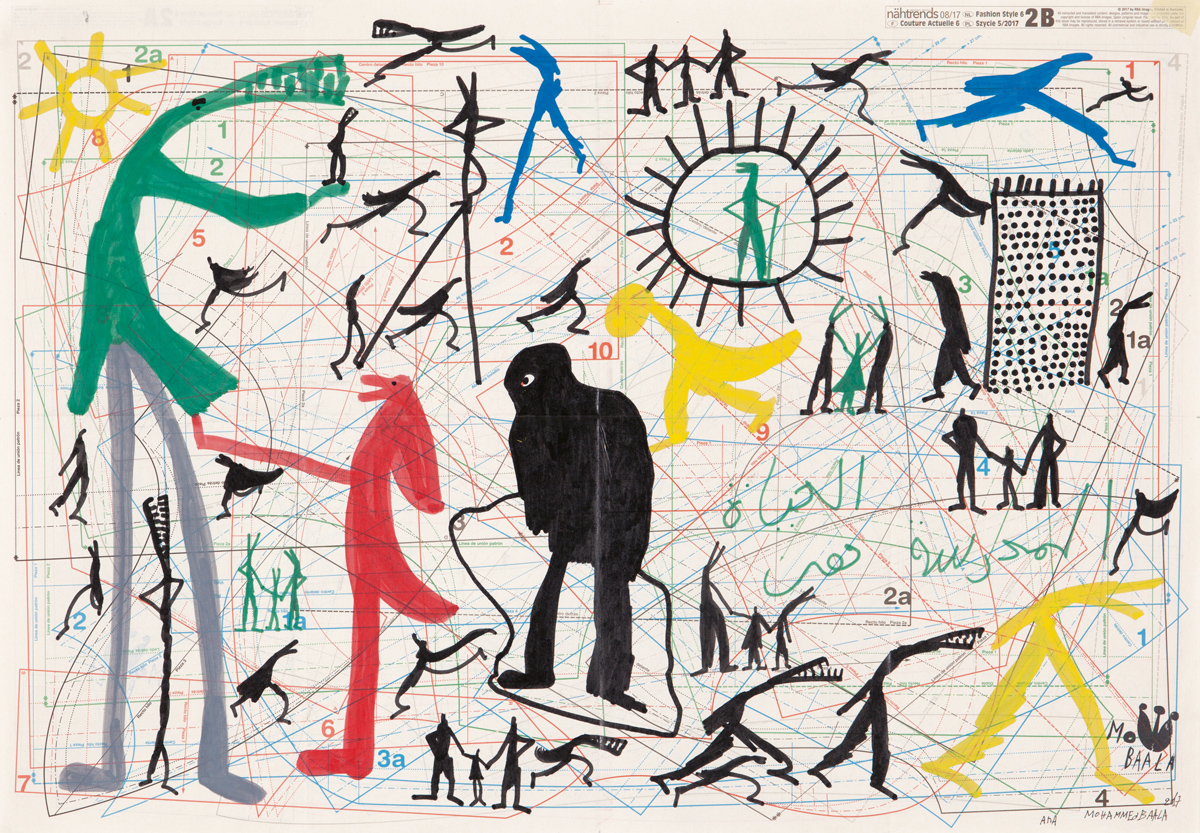

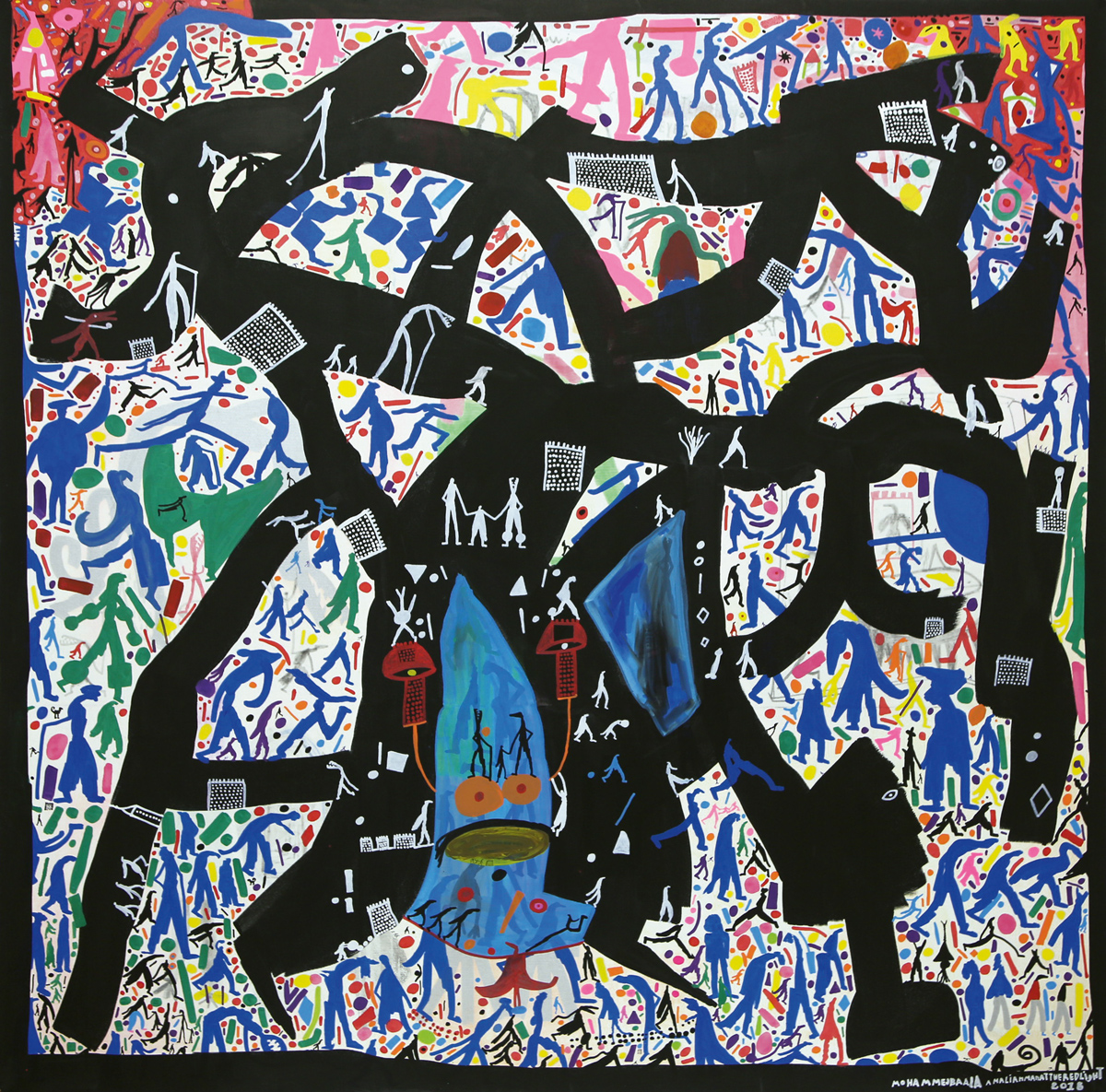

A visual representation of balance lies in a recurring motif in his work; the three figures that stem from his experiences with his parents as a child. Not only do the figures directly relate to his parent’s fighting, but to broader themes as well: “love and hate, peace and war.” He expresses how he has dreamt about bringing his family members together and so he attempts to unite them in his work. When a figure does not want to understand the others he turns it into an animal to downgrade it. He detests the autonomy and lack of co-operation the figure represents. Mo Baala’s work acts as a place of confluence for multiple polarities, he is always trying to mediate the oppositions and conflict. Mo Baala does this, not just with the figures in his work, but with any opposition he faces while creating, from choice of colour and material to the emotions he is experiencing. He revels in fusing complex oppositions, but all the while, as he states in a video for an exhibition a two years ago, “I try to say everything and I try to say nothing, to represent everything and to represent nothing.”

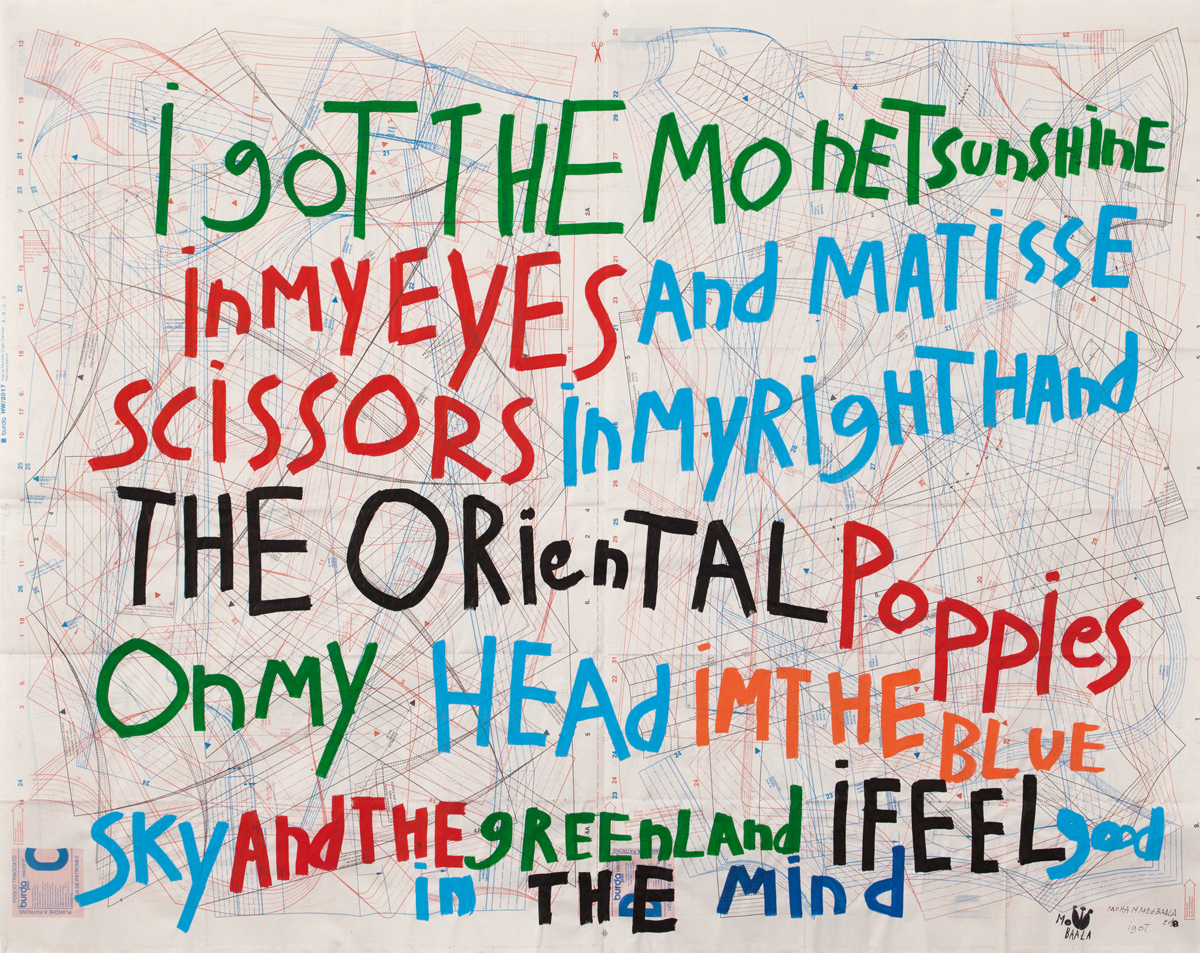

Two years on, Mo Baala has focused less on his experiences growing up and more so on his relationship with art and who he is in the creative process. Of course, the division of these experiences is not clean cut, particularly as Mo Baala started creating from a very young age. Mo Baala explains, “Life feeds art and art feeds life, you feel the balance between them.” He draws from both his own experiences as well as the experiences of others, “giving a value to everything and proposing questions” predominantly those of why and how. For him art is safe space to propose these complex questions, he describes it as “an adventure that is not dangerous” but equally, he elaborates, “you do not go on adventure if you do not feel powerful enough.” This adventure can take half an hour or several years because Mo Baala never lets a piece of work leave his studio until he is fully satisfied with it. Even if he loves a piece immediately, he is then confronted with liking it so quickly that it scares him, he feels something must be wrong and thus he must contemplate it further, the work is both “my heaven and my hell at the same time” he adds.

For Mo Baala, “being a good artist is to also be a good spectator, to know what quality is.” In order to feel satisfied with a work, to the point where it can leave his studio, Mo Baala has trained himself over the last several years to step away from the work and be a spectator with a different point of view. He describes it as a “serious democratic situation” in which you do not let your natural bias for your own work prevent you from critiquing it, this analysing can take a long time. Mo Baala stresses that he is not just critiquing the aesthetic, but rather the feeling he gets from the piece because that is what he wants his spectators to have. A feeling, whether it be with the subject, the material, whatever catches you, he wants you to feel something and to run with the possibilities. He believes that that is the relationship which “makes the work rich.”

Olivia Peterson